Ongoing Ukraine – Russia conflict could well be the straw that finally breaks the camel’s back. Slowly but surely battle lines are being drawn, awkward allegiances abandoned, muscles are being flexed, and old compromises and conflicts are being scratched back into existence. While Russia is being increasingly cut-off from the global community, it is finding allies in its own backyard with established resentment towards the current world order where the United States and its allies are considered the global pack leaders. Especially, the United States, with its status of being a Mecca of capitalism, and the self-appointed global policeman, has historically often been at odds with Russia. With the United States and its affluent allies in Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Africa clearly enjoying an economic advantage and thanks to pacts like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a higher grade of collective military security, their domination is configured to remain unchallenged. However, in recent times, some so called ‘antagonistic’ nations have started leveraging the unlimited reach and anonymity of the internet to level the playing field.

In June 2021, after critical infrastructure installation in the United States bore the brunt of suspected Russian cyberattacks in the previous months, US President Joe Biden “informed” Russian President Vladimir Putin that certain critical infrastructure should be “off-limits” to cyberattacks. Immediately, security analysts decried the futility of Biden’s efforts – that the idea of creating safe zones and ethical practices for online conduct is an improbability. A month later, the US and its allies – including NATO, the European Union, Australia, Britain, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand – accused China of instigating a global hacking spree. China fought this accusation – terming the claim as “fabricated” and asserting that it opposes all forms of cyber-crime. Further, the Asian powerhouse claimed that the US had got its allies to make “unreasonable criticisms” against China. Russian officials have repeatedly denied carrying out or tolerating cyberattacks.

Aside from communism, Russia and China have a lot of things in common. An unsure bilateral relationship with the US is definitely a Top-5 item on this list. As if to forge an alignment amid their status as ‘suspect’ countries in the US and its allies’ collective radar, China and Russia announced in June 2021 the extension of the China-Russia Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation. This could be interpreted as two regional powers building an Asian stronghold, importantly, there are also wider benefits: Russo-Chinese relations will be unsettling for the US and its Western partners, complicating strategic calculations, especially in terms of their strategies for the Asian continent.

A reportedly Russian hacking campaign involving SolarWinds – a supply chain attack on the latter’s IT performance monitoring system called Orion – resulted in the compromise of at least nine US government agencies and thousands of organizations around the world. This was followed by a far-reaching campaign exploiting a vulnerability in Microsoft Exchange Server to break into victims’ email inboxes and later propagate laterally across the organization. This was allegedly led by the suspected Chinese hacker group Hafnium. The collective toll of these espionage campaigns is still being assessed and according to researchers, it may never be conclusively affirmed. A wealth of the world’s intellectual data was tapped into, siphoned off, and the perpetrators and their alleged benefactors may have walked away scot-free.

Aside from financial motives and a sneaky way to benefit the organizations in their own country to match up to the evolving international standards, these exhaustive intrusions can be viewed as a means to question the status quo. Especially, challenging the US and European countries’ standing as global superpowers, champions of capitalism, and influencers to many Asian countries that are drawn by the former’s appeal and are not ready to view the realignment of power in favor of local behemoths Russia and China.

As of now, the Western powers are playing nice. NATO had underplayed the aforementioned situation by noting that its members “acknowledge” the allegations being leveled against China by the US, Canada, and the UK. Meanwhile, the European Union (EU) “urged” China to control “malicious cyber activities undertaken from its territory” – an ambiguous statement that implies that the Chinese government was itself innocent of directing the espionage. While the US has been much more specific – formally attributing intrusions such as the one that affected servers running Microsoft Exchange to hackers affiliated with China’s Ministry of State Security – the retaliation, according to official sources, could include economic sanctions and an executive order from the President to harden the federal government networks against future attacks. These sanctions, just as the many imposed before them, were not expected to be effective deterrents.

Could appeasement or leniency prove to be a roadblock here? While there is a line of thinking in the US administration that the usual sanctions are unlikely to force Russia or China onto the negotiation table, the fear is that calling these countries outright could elicit a strong cyber response. Many believe that the Russian and Chinese intrusions resulted in more than just espionage. Back doors have clearly been planted and the same can be leveraged at a future date for more destructive purposes, including modifying or wiping out critical data.

By all accounts, the next big war will be fought in cyberspace. US’s cyberattack on Iran’s missile system, the Russian company Internet Research Agency’s intrusion to spread misinformation through the US presidential elections, the ‘routine’ cyber compromise of mega-corporations leading to distinct societal impact, are all early hints that the powers-that-are have begun to consider the cyber route as a potent weapon. How long before the niceties are abandoned completely and a full-scale war – arising from accusations, sanctions, and isolation of problem entities, as is currently the case – will be underfoot?

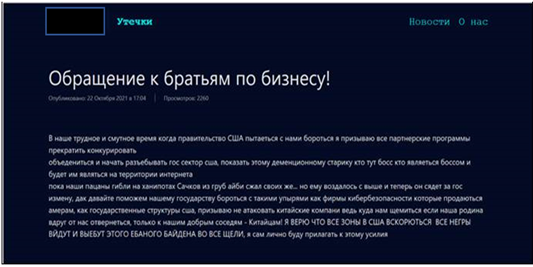

In October 2021, in response to the growing menace of ransomware attacks and to collaborate more on cyber intelligence, heads of governments and think tanks came together in what could be described as the unprecedented first step towards a global collective against cybercrime. The endeavor was spearheaded by the United States and involved 30 nations (including Japan) while ominously excluding both Russia and China. In a possible response to this and similar developments, CYFIRMA researchers monitoring a dark web forum observed ransomware operators unite as one against the US and its allies’ interests and potentially target them. Details of the post are provided below:

Loosely translated to English: “In our difficult and troubled times, when the US government is trying to fight us, I urge all affiliate programs to stop competing. Unite and start to destroy the state sector of the United States, show this dementia old man who is the boss who is the boss and will be on the Internet. While our guys were dying on honeypots Sachkov from rude aibi squeezed his own … but he was rewarded with higher and now he will sit for treason, so let’s help our state fight such ghouls as cybersecurity firms that are sold to amers like state structures of the USA, I urge you not to attack Chinese companies, because where do we need to worry if our homeland suddenly turns its back on us, only to our good neighbours – the Chinese! I believe that all zones in the US will cope all blacks will go and f**k this f***ing Biden in all the cracks, I myself will personally make efforts.”

The above post very clearly indicates the following pointers:

This isn’t an isolated incident. In the recent Ukraine-Russia conflict, the infamous Conti ransomware gang has fully backed Russia and promised retaliation if the West targeted Russian critical infrastructure. These examples highlight a deep nexus between organized cybercrime and governments willing to wield this strategic weapon, while simultaneously enjoying total immunity from possible repercussions via plausible deniability. While China, Russia, and North Korea are the most visible examples of this phenomenon, the trend is finding a lot of takers, especially in Asian countries. From Vietnam, South Korea, Pakistan, to India, everyone is eager to exploit cyberspace for their own agenda where real-world alignments and standings can be ignored in favor of who can compile the most potent and evasive malware code.

In modern-day geopolitical equations, every real-world conflict is likely to trigger the unleashing of more unresolved resentment. While Russia has tried to justify its stand on the Ukraine conflict on the world stage, it has found few supporters. Meanwhile, China has assumed a neutral position yet for observers, it is staunchly behind its closest Asian ally. Experts also note that the outcome of current Ukraine – Russia conflict, especially how the world governments respond and try to de-escalate this situation, could inspire China to handle its own ‘issues’ relating to Taiwan, Hong Kong, and disputed assets in the South China sea. On the sidelines of the Ukraine situation, Russia has already started talking about drafting a new “democratic world order” with China. With the availability of such a platform, other marginalized nations like North Korea and Iran – themselves alleged connoisseurs in the cybercrime game – are likely to join in and further divide the world into two distinct factions.